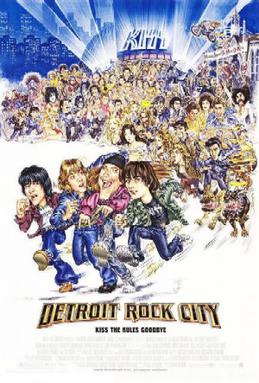

This week we watched Detroit Rock City, the 1999 teen comedy. This 95 minute film was directed by Adam Rifkin and grossed $4,217,115 out of its $34,000,000 budget. Wow. The journey of these four boys, Hawk, Lex, Trip, and Jam, is a little crazy. Albeit there were a few issues with continuity, but if you suspend your belief a bit you still manage to follow the film just fine. The boys have to see KISS, there was no real option there. However, the things they have to do to see the band are crazy, yet I was laughing the whole time. It was really hard to take them seriously. The film was overall pretty funny, feigning on the idea of being a bit much. I really enjoyed watching each of their journeys, even Jam’s overbearing mother, come together in this long story-line to go see a KISS concert.

This week I got to present one of our readings. My reading was “Classical Hollywood Cults,” by Ernest Mathijs and Jamie Sexton. This ten page reading was really interesting and worked really well to tie in major themes of classic Hollywood cults. The major themes that made up the classical Hollywood cults were nostalgia, gaiety, intertextuality, forms of labor, and violence.

Nostalgia is a sense of yearning for a better time, or home. Nostalgia also became the yearning for that initial impression of a film left after the “first time” exposure of a film. This “first time” nostalgia sets classical Hollywood cult viewers apart from the other cultists. You can never get a first take on something again, but it’s so much more than that. This first time is also really important to the “true” capture of the film, focusing on originality and reality. In the mid-1950s nostalgia stops having an impact on the present and from then on only relates to the definite past. This sense of nostalgia is reinforced by what they called time travel, essentially interrupted by flashbacks or songs and it is sometimes over-cluttered with the past, to the point where the story cannot progress functionally. This is really important. Nostalgia is a key factor in almost all of the other parts that make up a classic Hollywood cult.

Something I found really interesting was the discuss on types of labor. Basically, the kinds of labor or perceptions of labor are prone to attract fan devotion through their imperfect fit within, and challenges to, the system. The labor of stars with cult reputations of the classical era are drenched with the impression that they stand for a “truer” kind of “professionalism, sophistication, glamor, or charisma from a time when such qualities were said to be of a more pure constellation” (187). Their focus on the category of labor, that was deemed to have the most cult appeal, is that of a child actor as it combines the innocence and purity associated with the child and the mental and physical endangerment of their well-being by Hollywood. This debate on innocence and purity versus the perverse adult world of Hollywood don’t coincide, which is what makes child actors such a big deal. They are opposites, yet the same all at once, which could describe classical Hollywood cults in a nutshell because they are mainstream and marginal, and center and periphery at the same time, both of which contradict the other.

If there was only one other thing you can take away from the reading I’d pick the impact of television on the classic Hollywood cults. From the 1960s onwards, and particularly through the 1970s and 1980s, television gradually replaced the repertory theater. Television became the main form of family entertainment, and it also became the medium classical Hollywood cults migrated to. Seasonal television re-runs, and occasional theatrical re-releases, add to the already nostalgic-heavy long-term receptions of classical Hollywood cults. The consequence of this development has been a gradual disappearance of classical Hollywood cults from the studies of cult cinema. . “Peary’s first volume of Cult Movies (1981) lists 41 classical Hollywood films, out of a total of 100. In his subsequent collections that ratio declined drastically” (193). This narrowing of the perspective also affects how some of the themes of classical Hollywood cults highlighted, such as gaiety, or nostalgia, are remembered. “The danger exists that classical Hollywood cults will soon be cast out of considerations of cult cinema altogether. Before long the current nostalgia within classical Hollywood cults may soon be replaced by a longing for classical Hollywood cults” (193).

I feel uptight on a Saturday night

Nine o’ clock, the radio’s the only light

I hear my song and it pulls me through

Comes on strong, tells me what I got to do

I got toGet up

Everybody’s gonna move their feet

Get down

Everybody’s gonna leave their seat

You gotta lose your mind in Detroit Rock City

Hey Chelsea! Great blog again. You did a wonderful job presenting your reading for this week too. The most unrealistic parts of this movie were scenes involving women. Every girl just swooned over their respected ‘love interest’. What are the odds that Jam’s crush finds him, confesses to him, and then they have sex? Or how about the girl they picked up, who was well written up to the point of her kidnapping, acting like a damsel until Lex ‘heroically’ saves her and the car? Not the best portray of female characters, by any means. But a fun film all the same.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You talk a lot about nostalgia and how it ties into this week, so did you find the movie to be nostalgic? Personally I just didn’t connect to it in that sort of way. I don’t know what it is, if maybe the journey was just too pointed for me to connect with, whereas Dazed and Confused was sort of more open? I’m wondering if it’s just a me thing.

LikeLiked by 1 person