Detour is an interesting reflection on the career of its director, Edgar Ulmer, and how his estrangement from the film industry eventually created the hasty film that’s been appreciated for the very qualities that made it a B-movie at the time. Ulmer’s blackballing from the film industry made him an outsider, but also gave him more range to work with in the B-movie industry as it was less censored and allowed for more artistic liberties to be taken. Having worked under many European luminaries at the time, Ulmer had a language in film that was dreamlike and dramatic. His ability to produce a movie in two weeks with minimal set, but the simple employments of light and fog to mimic the cliche settings of the time were all parts of how the explosive but underfunded story managed to carry the film to cult status. Paracinema is a concept I’m familiar with; we studied elements of it in a sophomore art history class that focused on video heavily. It was film acting outside of accepted film, which included video art that followed no plot or was made for visual purpose only. I hadn’t considered this would also include movies made outside of popular acceptance and deemed “trash movies” by elite film culture. Ulmer was working in this industry having already been amongst the elite, and was able to project his ideas with minimal funds and more raw ideas to carry the film. I have a great appreciation for B-movies, largely because they follow no pre existing structure, and often don’t cater to audiences very well making them much more exciting and visceral in that they’re made beyond the sake of profit; or they are so strongly trying to identify as a trope to make money that they parody themselves. This context is what makes the frenzied plot of Detour even more illuminating, and it’s elements of film noir incredibly blunt to watch.

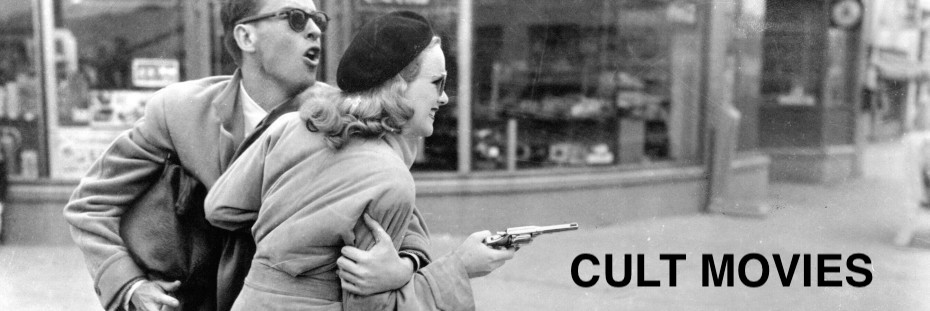

my favorite shot!

Detour is immediately a biased film, as the narrator is shown to be unreliable and self-depreciating. It gives an interesting insight to what men will do to justify their problems, as Al Roberts would blame anything in the world but himself for his bad luck. While he feels righteous in his decision to go to see his girlfriend in the west that left him to be famous, this chase is what bring endless amounts of bad decisions on his part and the eventual murder of two people. Throughout the movie however, Al continues to insist that fate is what leads to this terrible misgiving of people “just dying around him” when the reality is that he very much participates in making these decisions to follow his goal of the fame his girlfriend will bring him. Vera is the only character that sees through his pathetic guise and constantly holds him to his actions. While she was probably considered venomous at the time, when women were undermined for having such boisterous characteristics, she is the most honest character to discover what Al Roberts is really like. I loved the wide-eyed, crazed look she holds while delivering her lines a mile a minute, she’s a heroine that I would be intimidated by today.

great use of “crazy eyes”, what a lady

Her explosive character is killed as angrily and quickly as she appears by Al’s own greed for the inheritance of another guy he “didn’t kill”. He also thinks that her death was an accident, thus making both Haskill and Vera’s death almost imaginary in that his real identity never is associated with them. It causes the audience to wonder if what’s being portrayed is what actually happened or simply through the eyes of a self-absorbed man who thinks the world is out to get him. Is Sue even real? Is the goal of wealth and fame personified to be a love interest that can never really be reached by the protagonist? Could coincidences like the death of two people really happen? Or is Al Roberts a man that justifies doing bad things because he’s a narcissist? It’s 1945.