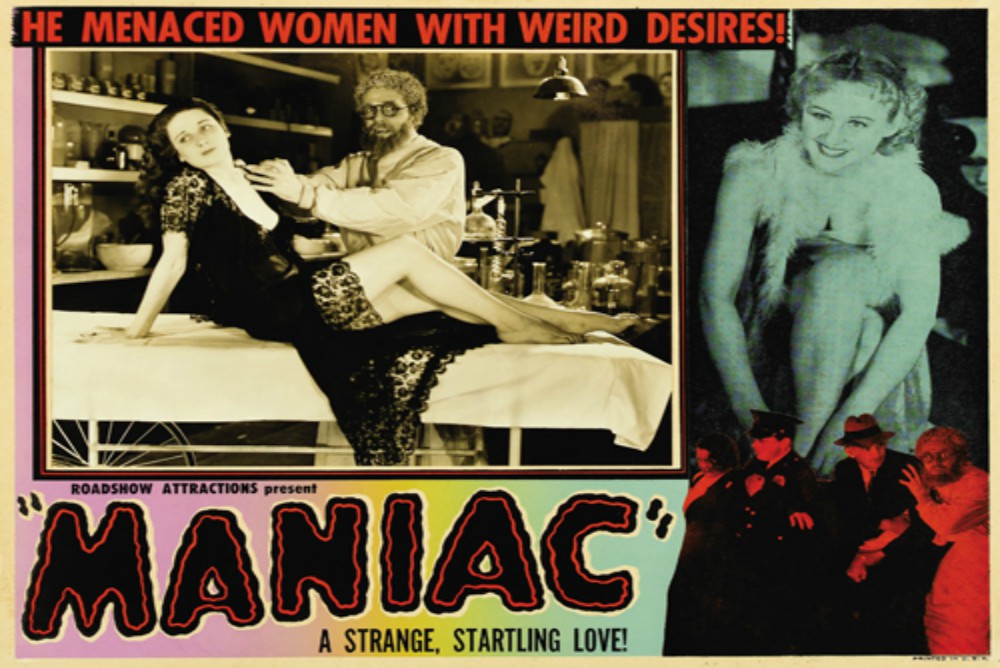

Debates surrounding cult cinema most often address how a cult film breaks boundaries of morality, challenges prohibitions in culture, disputes commonsense conceptions of what is normal and acceptable, and how as a result they confront taboos. - Mathijs and Sexton

“Transgression and Freakery,” an excerpt from Cult Cinema: An Introduction by Ernest Mathijs and Jamie Sexton, highlights two common ways that cult cinema confronts taboos. A taboo is “a cultural prohibition, an act seen as morally wrong.” Often seen as reflections on the contamination of perceptions of purity, taboos generally tend to be bodily fluids. As Douglas says, “the traffic between the inside and outside of the body correlates strongly with what cultures see as taboos. A crucial element here is that of any substance that allows for the crossing of borders between the inside and outside of the body.” Such substances include tears, sweat, blood, pus, urine, semen, spit, menstruation, lactation, or feces.

For a film to be considered transgressive, it has to violate law or morality – it must pass beyond the limits imposed by society. Water’s 1972 exploitation comedy, Pink Flamingos, is a movie that has no sense of boundaries. Although exploitation has become harder to execute as it forges with mainstream cinema culture, Waters film is still as transgressive today as it was then. Even if you rule out certain elements that our society may have become desensitized to, such as nudity, masturbation, and incest, Pink Flamingos still touches on a variety of taboo topics: rape, cannibalism, the consumption of feces, etc. Transgression can take place in terms of content, attitude, or style; however, regardless of how it achieves transgression, this idea lays at the center of the construction of cult films.

“It still works, I know that. It didn’t get nicer; it might have even gotten more hideous. Even people who think they’ve seen everything are sort of stunned by it. They may hate it, but they can’t not talk about it. That was the point. It was a terrorist act against the tyranny of good taste.”

– John Waters in an interview with Vanity Fair, discussing Pink Flamingos forty-five years after its initial release (2017).

Waters chose to approach transgression by directly challenging good taste, which I feel makes this film transgressive in every aspect of the word. The content, which centers around characters who are literally fighting for the title of “the filthiest person alive”; the attitude, with Waters purposefully trying to outrage the masses; and the style, which is nothing if not competently excessive in every regard – each of these mediums on their own would have laid the groundwork for a cult film, but when paired together, they create a film that is almost timeless in its reception.

The transgression of reason -which J.P. Telotte describes as “the love for unreason” – is an incredibly important aspect of how a cult film is received. When a film confronts and embraces taboos, when it crosses boundaries of time, custom, form, and good taste, it violates our sense of the reasonable; and this is exactly what appeals to the film cultist. We’re allowed to vicariously delve into dangerous territory, but when it’s all said and done we can fall back on our reality – a world of reason. Transgression in a film challenges our ideas of morality, it puts us into a world of “what ifs,” and it sheds light onto an aspect of human nature that isn’t deemed pretty enough to be reflected in mainstream cinema. I feel that this explains why Pink Flamingos was such a cult hit then, and why it still packs a punch today. None of us want to be Divine, but we’re enthralled by her and by the world in which she lives, because both directly challenge everything we know not only about our own world, but about ourselves and the societal standards that have always been imposed on us.

In the words of John Waters, "Get more out of life. See a fucked up movie."