This past week in our Cult Film class, we started off our week with a screening of Blacula, and we discussed and learned about the era of blaxploitation in cult films. Blaxploitation can be defined as an ethnic subgenre of the exploitation film, which came about in the early 1970s. These films were very popular among a variety of communities, however, often were found to face a great deal of backlash for the stereotypical nature of the films which at times showed the characters having questionable motives in the plot of the films, including playing roles of criminals. This genre is among the first which move black characters and black communities to the front of the screen of film and television rather than just hosting them in a film as sidekicks or villians, or even victims, rather these characters are the main focus in these types of films. This coincides with the rethinking of race relations which took place in the 1970’s in America.

Blaxploitation films (also called blacksploitation films) were aimed originally at an urban African-American audience, but this genres appeal soon broadened to cross lines of race and ethnicity. There was a realization in Hollywood of the profits of expanding these films to viewers of other races and ethnicities, pushing these films to become more mainstream than thought possible in the past. Blaxploitation films were the first films to feature soundtracks of soul and funk music, giving this genre a unique sound, pushing the boundaries of the uniqueness of the genre across the board, making it intriguing for a variety of cultures. The blaxploitation film which we screened this week was Blacula.

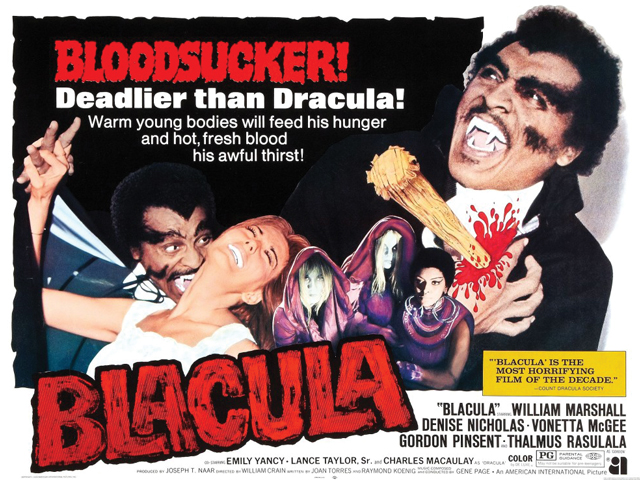

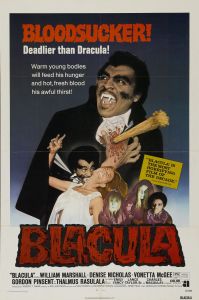

Blacula is a 1972 American blaxploitation horror film which was directed by William Crain, who is named as one of the first black filmmakers from a major film school to achieve commercial success. Blacula stars William Marshall who plays the main role in the film as an 18th century African Prince named Mamuwalde. It also stars Denise Nicholas, Vonetta McGee, Gordon Pinsent, and Thalmus Rasulala. In the film, Mamuwalde is turned into a vampire after he is bitten by the one and only Dracula himself, and is locked in a coffin in Dracula’s castle in Transylvania in 1970 after Mamuwalde asked for help with supression of the slave trade, and Dracula refused. Luva, Mamuwalde’s wife (played by Vonetta McGee) is also imprisoned and left to die in the room with her husband. The film then fast forwards to the present day world where Mamuwalde is released from his coffin into the world as a vampire. He meets a woman who is identical to his past wife and falls in love with her. The film follows his experience as a crazed bloodsucking killer who attempts to keep the woman he is in love with while also fixing his cravings by turning the people around them into vampires. Blacula received mixed reviews after its release, however, it turned out to be one of the top grossing films of the year. It was followed by its sequel, Scream Blacula, Scream in 1973, and inspired a wave of blaxploitation themed horror films.

Blacula is a 1972 American blaxploitation horror film which was directed by William Crain, who is named as one of the first black filmmakers from a major film school to achieve commercial success. Blacula stars William Marshall who plays the main role in the film as an 18th century African Prince named Mamuwalde. It also stars Denise Nicholas, Vonetta McGee, Gordon Pinsent, and Thalmus Rasulala. In the film, Mamuwalde is turned into a vampire after he is bitten by the one and only Dracula himself, and is locked in a coffin in Dracula’s castle in Transylvania in 1970 after Mamuwalde asked for help with supression of the slave trade, and Dracula refused. Luva, Mamuwalde’s wife (played by Vonetta McGee) is also imprisoned and left to die in the room with her husband. The film then fast forwards to the present day world where Mamuwalde is released from his coffin into the world as a vampire. He meets a woman who is identical to his past wife and falls in love with her. The film follows his experience as a crazed bloodsucking killer who attempts to keep the woman he is in love with while also fixing his cravings by turning the people around them into vampires. Blacula received mixed reviews after its release, however, it turned out to be one of the top grossing films of the year. It was followed by its sequel, Scream Blacula, Scream in 1973, and inspired a wave of blaxploitation themed horror films.

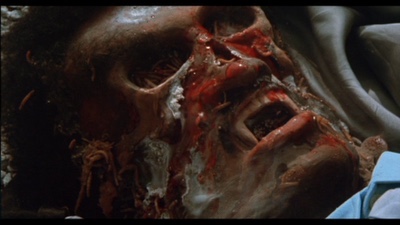

But because this week has been about Blacula, I’m speaking about vampires specifically. Blacula is a great example of a changing approach taken for the portrayal of monsters, who begin to become dynamic characters. The reading “Deadlier than Dracula!” states that monsters were typically used to elicit pity in early horror stories, including their film adaptations, taking on the trope of a “good-hearted sacrificial lamb”. While Blacula uses Dracula’s character within the movie, it differs from previous monster films within the horror genre because the monster’s sole purpose is no longer to make the audience feel bad for them. Instead Blacula’s character, Mamuwalde, acts as a leader and revolutionary; he is a hero of the mistreated, standing up to their opposers. Harry Benshoff’s “Blaxploitation Horror Films”, discusses the role of the monster within the blaxploitation horror genre well:

But because this week has been about Blacula, I’m speaking about vampires specifically. Blacula is a great example of a changing approach taken for the portrayal of monsters, who begin to become dynamic characters. The reading “Deadlier than Dracula!” states that monsters were typically used to elicit pity in early horror stories, including their film adaptations, taking on the trope of a “good-hearted sacrificial lamb”. While Blacula uses Dracula’s character within the movie, it differs from previous monster films within the horror genre because the monster’s sole purpose is no longer to make the audience feel bad for them. Instead Blacula’s character, Mamuwalde, acts as a leader and revolutionary; he is a hero of the mistreated, standing up to their opposers. Harry Benshoff’s “Blaxploitation Horror Films”, discusses the role of the monster within the blaxploitation horror genre well: