Cult films or ‘cult classics’ are a unique area in film studies. While many audiences can identify a cult film, few can precisely define it. Is a cult film something so badly written it’s outrageously funny? Is it a plot so berated with plot holes that fans surprisingly enjoy it more, welcoming the open interpretation? Or is it simply a movie that while failing in the box office reviews, found success in the adoration and nostalgia of audiences around the world? While film scholars debate on a concrete definition of cult films, there are several notable criteria that help identify this unique film niche.

“The Cult Film Reader”, edited by Ernest Mathis and Xavier Mendik, identifies four major elements in a cult film: anatomy, consumption, political economy, and cultural status. While not all of these criteria may be found in a cult film, they represent the standard. Each of these elements can be broken down even further. Let’s look at the consumption of a cult film. This is how the film is received by fans and critics. Say you got bored one night, called a buddy over, and challenged him to a drinking game while watching Lord of the Rings. A few weeks later that buddy returns with more friends ready for round two. This would be an example of active celebration. If it now becomes a tradition to marathon Lord of the Rings and take a shot every time the ring gets a close up, then you have created a ritualized celebration of the film. This unique way of experiencing the film is a key example of audience communication.

Let’s continue this example a bit further. It’s been a few years since you’ve seen you pal when you get a call from him. There’s a one night showing of Lord of the Rings next week, and wouldn’t be great to dress up as the characters and catch up for old times’ sake? When you arrive at the theater the place is packed with fat Gandalf’s, miniature Legolas’, and more Frodo’s than you can count. Such a diverse grouping of people, and yet you’re all together to celebration one film. You’ve joined a community, a fandom, around a film that all of you adore for your own reasons. Communities or followings of a film are a critical feature in cult cinema. After all, what makes cult classic’s so unique and special is the people who celebrate it. But what is more important? The film or the audience? There are two philosophies that encourage this question: ontological vs. phenomenological approach. The ontological approach looks at the context of the movie to determine what give it it’s cult like following; the plot, direction, exploitation elements, etc. Phenomenological approach instead looks at cultural context. In other words, this approach looks at how the film is received, by whom, an in what way.

(Seriously that bunny thing is just terrifying.)

So now we have a brief understanding of the study of cult films. But just how long have cult films been around? A better question maybe ‘what was the first exploitation film’. American Grind House, a documentary first released in 2010, explores the history of exploitation cinema in vivid, uncut detail. Exploitation is defined as ‘the use of something for profit’. This ‘something’ is often seen as taboo, disturbing, or socially unacceptable. Dwain Esper, a film director in the 1930’s is considered by many to be the grandfather of exploitation cinema. Maniac, his most infamous film could also be considered one of the first cult films. From over acting to bizarre camera angles and obvious plot holes, Esper’s work was considered by many to be the worst in cinema. However, Esper used the exploitation of mental illness to draw in his own unique fan base. A common staple to exploitation films is the promise of showing something a ‘respectable’ film studio would never include in their movies. Esper got away with releasing Manic, a film full of animal abuse, nudity, and rape because he claimed the film was educational. In random parts of the film Esper would through in an ‘informative’ paragraph discussing the martial state of ‘maniac’. However, even these crude out of place cuts added to weird humor that comes with Esper’s films. The sense that you’re watching something so bad, its almost revolutionary.

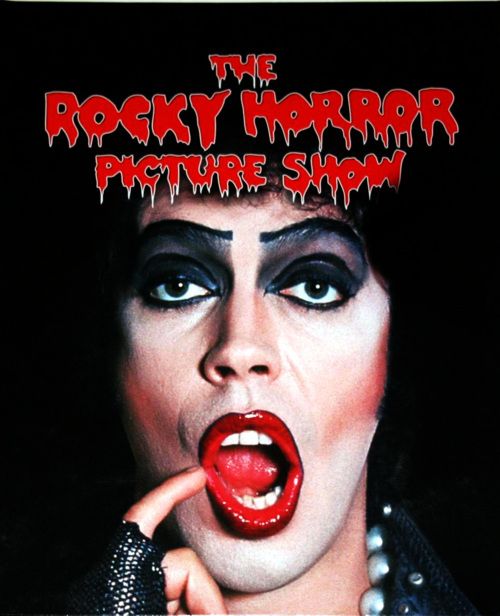

This semester we will discover what separates the cult classics from the rest of cinema. From ridiculously cheesy lines that add to the humor in The Room to the catchy seduction of Rocky Horror Picture Show, this semester is sure to give us a better understanding of what makes a cult film truly unique.